In recent years, the term “mindfulness” has entered popular culture. Articles, books, workshops, and apps abound to bring mindfulness into every possible context. But why is it so important to be so intentional about things? What good is mindfulness really, aside from just being more conscious?

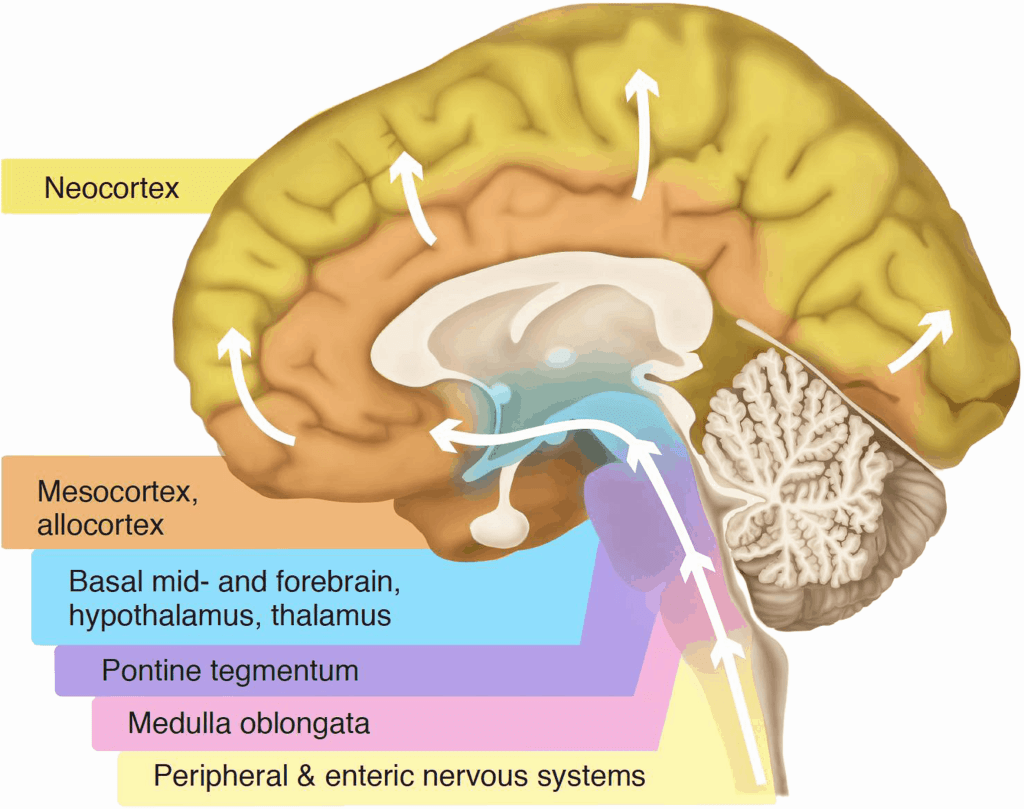

The conscious part of our body – the neocortex, or “new layer” of the brain – is indeed a new innovation in the history of our species. It evolved in response to a set of changing circumstances, including a cooked diet (subsequent to our mastery of fire), fabrication and use of a continuously growing toolkit, and (most importantly) our use of language.

The rest of the human body is, in essence, the same animal we used to be before growing a neocortex. Taller and with greatly increased manual dexterity, to be sure, with smaller teeth and an expanded cranium – again, long-term effects of better nutrition in tandem with technological advancement. Less hairy, perhaps; otherwise, pretty much the same creature.

This creature, like other animals, operates at a largely unconscious level. Its urges and impulses direct its behavior in order to maintain homeostasis (a default state of vital function), seeking food, shelter, or climate as needed. At the root level of the brain, stimuli are interpreted in one of two ways: opportunity (to obtain food, a mate, social status, etc) or danger (triggering the “fight-or-flight” response). This is important to remember: whatever we may be doing with our conscious mind, the crocodile lurks below the surface, always seeking to identify opportunity or danger. As long as we are not acting at the direction of mindful intention, we will be “on autopilot”, functioning according to our natural survival instincts.

Our survival programs served us well as long as we lived among the animal kingdom. Life in the wild is always on the edge of survival. For the last few hundred millennia, though, we have been changing the world to make it more accommodating for ourselves. We no longer live on the edge of survival, but produce an abundance far beyond the necessary. In the 21st century, the problem is not finding food and shelter but avoiding the clamor of advertisements for food, shelter and every imaginable luxury and novelty item. The complexity of our society is such that we face not the occasional leopard or bear or hostile tribe, but an unceasing bombardment of trivial and non-trivial stressors. Although we have altered the circumstances of our environment, our unconscious selves still run the same old program, so to speak. We are primed to identify opportunities to consume, to pick out deadly threats in time to respond with a hormone-induced surge of energy.

In the context of our artificial lifestyle, our default programming no longer works to keep us alive, but ends up causing us all kinds of harm. Our food-seeking automation, in the presence of endless supplies of heavily marketed high-calorie food, has turned obesity and diabetes into a leading cause of death for humans in industrialized countries. That useful danger-scanning function keeps us constantly on edge, overreacting to non-critical sources of stress like work deadlines and tax paperwork as if they posed clear and imminent threats to our lives, and consequently stress-related health problems are another leading cause of death.

By practicing mindfulness – taking mental note of our reactions to our own sensory perceptions – we not only heighten our awareness of the processes that drive our automatic reactions, but we also slow those responses sufficiently to give ourselves a better chance of acting with intention. The more of our behavior consists of intentional action, the less likely we are to react inappropriately to the kinds of events that make up our daily lives apart from the world of survival in the wild.

Since the beginning of human thought, the strangeness of our own human condition has made us wonder. We are, as Plotinus said, poised midway between the gods and the beasts. What is a god but one who possesses freedom of will? When we act with intention, we exercise the divine power of choice. But we are only really ourselves when we act mindfully. At other times, we are leaving the beast in charge – a fine beast, certainly – to quote Hamlet, the paragon of animals – yet no more than an animal. It is only in our moments of conscious intentionality that we are free to be, rather than to be played. Simply put, to be mindful is to be fully human.