Yoga and King Arthur may seem as related as apples and bricks; nonetheless, exploring that relationship is our task today. In order to provide context, we must allow a brief digression on the nature and history of religious thought.

All religions are symbolically represented systems of psychological knowledge and experience.

All human psychology deals with the same processes of ideation, perception and reflection; these processes involve the same structures in the brain and a common set of emotional and mental modes of experience. Throughout the long dawning of consciousness from the Paleolithic to the present, marked by the evolution of language and art, human societies have recorded the struggle to understand the nature of this consciousness, and to find meaning in the search. This is the origin of all human religion.

The period we call the Bronze Age saw the rise of the first empires and, quite naturally, the first use of religion as a unifying element on a multisocial scale. The “classical” or Mediterranean religions are all syncretistic agglomerations of previously existing local cults and regional traditions, rewritten and to some extent sanitized by subsequent orthodoxy. Each great Bronze Age culture developed its own official religious system, some of which have survived into the present – but they are all rooted in the same basic methods of addressing the same set of existential questions produced by human minds operating with the same perceptual and cognitive equipment. The difference between religions is not, as some would have it, a matter of unique divine revelation or sole possession of truth; it is like the difference in cuisine or music from one culture to another. The end results may be diverse, but the same principles of heat and chemistry, or of rhythm and tone, apply universally and for a common purpose. (Interestingly, neither cuisine nor music have been the source of any wars, persecutions or genocides; religion alone among cultural artifacts bears that distinction.)

We humans tend to think in terms of labels. Most of the perceptions that make it through to our conscious mind are immediately classified; anyone who wants to experience an example of this process may sit for a moment and try to simply perceive the surrounding world without mentally naming anything or using any form of the verb “to be”.

Because of this tendency to pigeonhole our perceptions of the world, we often fail to recognize the basic sameness of ideas that manifest across diverse cultures, focusing instinctively on superficial differences. One such idea holds an important place in the thought-space of both European literary history and Asian spiritual practice: Bhakti yoga. “Bhakti yoga” translates roughly to “union (with the Divine) through adoration”, and is equivalent to the medieval European concept of courtly love, familiar to students of the Arthurian legend.

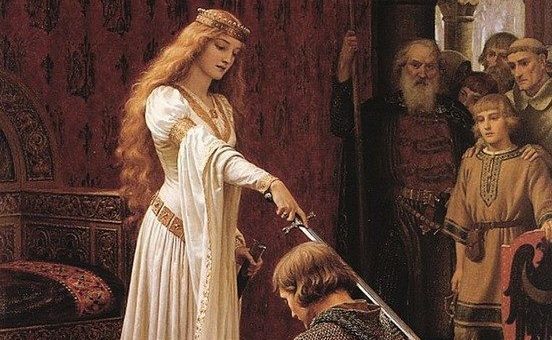

Around the 12th century, the idea of “courtly love” appeared in European culture, initially as a theme for wandering troubadours and court minstrels, and eventually finding its place in the romanticized histories of medieval literature. In the stories that remain – among which the Matter of Britain in all of its iterations looms large – courtly love is the knightly practice of fixating upon a woman to adore, to whom all of the knight’s endeavors are dedicated and to whom is to be attributed all the glory of his successes. This idealized woman was supposed to be superior in social rank; the more so, the better. You see, the purpose of courtly love was not to achieve consummation (although the frailty of human willpower in opposition to our animal urges was, without a doubt, as much a factor in this context as in any other) or any kind of physical union at all. The objective was to find an unattainable goal, then leverage natural desire to motivate the individual towards “being worthy” of the love of the chosen object of devotion. This process of self-improvement, if pursued with the fanatical single-mindedness normally reserved for lust and vengeance, was supposed to result in the transcendence of the practitioner.

By fixating on an idealized and entirely fictitious conception of an unknown person, the knight effectively invoked the Eternal Feminine as an ally. The woman chosen as the object of adoration was not the real woman at all, but the knight’s highest possible conception of Woman. As the knight improved himself, his devotion to the Eternal Feminine was supposed to develop into respect for women in general. A word about gender as long as we are talking about knights and the Eternal Feminine: it should go without saying that the patriarchal context of medieval European literature has nothing to do with the actual practice in question; neither the practitioner’s gender nor that of the object of devotion are of any importance.

However unreliable the effects may have been upon the behavior of individual knights, there is no denying the transformative power of the idea of courtly love. In his masterpiece The Once and Future King, T.H. White explores the social effects of courtly love at some length, as an alternative to the old system of “Might makes right”: a civilizing, gentling influence upon medieval European ideals of masculinity and the right use of power. Chivalry – which initially meant simply knighthood – came to stand for a code of ethical behavior that proscribed violence against women and children, emphasized the rule of law, and favored mercy to a fallen opponent. White drew extensively upon medieval literary sources for his work, and students of the period will be familiar with the real shift in the treatment of female characters in the period literature. Likewise, it can hardly be a coincidence that the Virgin Mary’s role in religion and popular culture evolved over roughly the same period of time as the spread of courtly love – although it would be a bit much to suggest a causal relationship in either direction. Be that as it may, in the early Middle Ages Mary was venerated as a mere vessel, the Blessed Virgin Mother of God; by the fourteenth century, she was the Queen of Heaven and cathedrals were being built in her honor all across the European continent.

Now for the yoga connection. Yoga derives from the same Sanskrit root as the English word “yoke” as in a yoke of oxen, linked together for common purpose. Yoga is one of the most ancient spiritual practices and has evolved into a wide variety of schools and disciplines, but all are based on the idea of aligning and coordinating the components of the human individual for united and effective action under the aegis of the enlightened will. In the Western world, most of us are familiar with the physical fitness aspect of yoga, or Hatha yoga. A healthy and equilibrated body is the best support for a sound and flexible mind, so Hatha yoga is a natural entry point to an effective process of self-development. The other yogic disciplines expand on the basic techniques of self-control, applying them to the mind as well as the body through a number of different practices. One of these disciplines is Bhakti yoga: unity through adoration.

In Bhakti yoga, the practitioner chooses a divinity upon whom to focus devotion. As with courtly love, the identity of the divinity is not the main thing; the intention is to infuse oneself with the perfect essence of the chosen object of adoration. As any conception of a deity is formed entirely within the consciousness of the practitioner, the deity is – in psychological terms, a projection of the practitioner’s highest values and ideals. By focusing on love of these ideals, the concepts themselves become clearer and the self is drawn towards being a living embodiment of them. The divine qualities of a god become personal goals to strive for.

Any discussion of yoga as union will eventually turn to sexuality as a metaphor for the union of the divine and mundane components of the human being. This is a central idea in Western as well as Asian spirituality, although it has been more thoroughly resisted and suppressed by orthodox religious authorities in Christendom than elsewhere. Despite the best efforts of Western puritans, the role of sexuality as a healthy and necessary part of the human being has found its way into mainstream psychology.

Carl Jung defined libido as a specific kind of personal power or energy that can manifest naturally in an erotic (which is to say, essentially creative) direction, but can also be channeled into personal pursuits – again a creative act of will. This idea of libido conceptually links sexuality and personal creative power aside from biological reproduction – a tenuous relation perhaps; nevertheless it is reflected in many traditions from around the world and throughout history. Both Taoist tradition and Tantra yoga focus on retaining, controlling, and channeling erotic energy for purposes of spiritual development. Modern Western mystical traditions, notably the Golden Dawn and various Crowleyite offshoots, teach and practice similar disciplines, openly citing inspiration from Hindu religious thought. Medieval Christian mysticism is replete with plainly erotic symbolism, and in fact may have contributed to the development of courtly love as a spiritual practice. The same kind of metaphor is found in medieval Islamic writing; there is good evidence of these ideas having been brought from the Middle East to Europe by returning Crusaders. One can hardly speak of returning Crusaders bearing Islamic esotericism without mentioning the Templars, who were eventually stamped out by the religious orthodoxy on accusations of heresy – in this case, meaning an open-minded approach to the concept of religions being cultural constructs that hide psychological truth in symbolism that can be understood by those with the ability to understand. Which is, by the way, perfectly in line with what Christ is to have said in the Gospels, repeatedly, to the effect of “let those see, who have eyes to see”.

Of course, this is exactly what threatens the orthodoxy: their hold on temporal power depends on possession of The Truth – and on the rest of society buying into that belief. Monopolies generally dislike competition. Interfaith collaboration in deconstructing symbolism is beyond their ability to imagine. Nonetheless, knowledge will never be anyone’s exclusive possession, and tradition eventually makes way for new learning.

Did Bhakti Yoga ever become mainstream in Western culture? There can be no doubt: the display in the average 20th century home of a portrait of Christ, or of crosses – empty or occupied – was a common sight across Christendom. As religion increasingly loses its influence on popular culture, images of celebrities replace sacred icons in private as well as public places; but as long as adoration leads to personal development, the effect is the same. Whether your personal aesthetic favors King Arthur or Asian traditions, inspiration can fuel your journey of self-realization.

Well met and Namaste.