Language, like the tools of science, is a remarkable artifact of human invention. It is not merely a means of communication but a sophisticated instrument akin to a microscope or a telescope. Just as these devices bring distant or minuscule aspects of reality into sharp focus, language allows us to isolate, analyze, and manipulate information about the world around us. When we describe something with words, we are, in essence, bringing it under the lens of a linguistic microscope, magnifying a particular aspect of our experience and rendering it in precise detail.

However, as with any tool, the power of language comes with inherent limitations. By focusing so intently on one part of reality, we inevitably separate it from the whole. When we name, define, or categorize something, we create a conceptual boundary around it, carving it out from the seamless web of existence. This act of separation is artificial, yet it is necessary for understanding and communication. The world, in its vast complexity, cannot be fully apprehended all at once, so we break it down into manageable pieces, using language as the chisel.

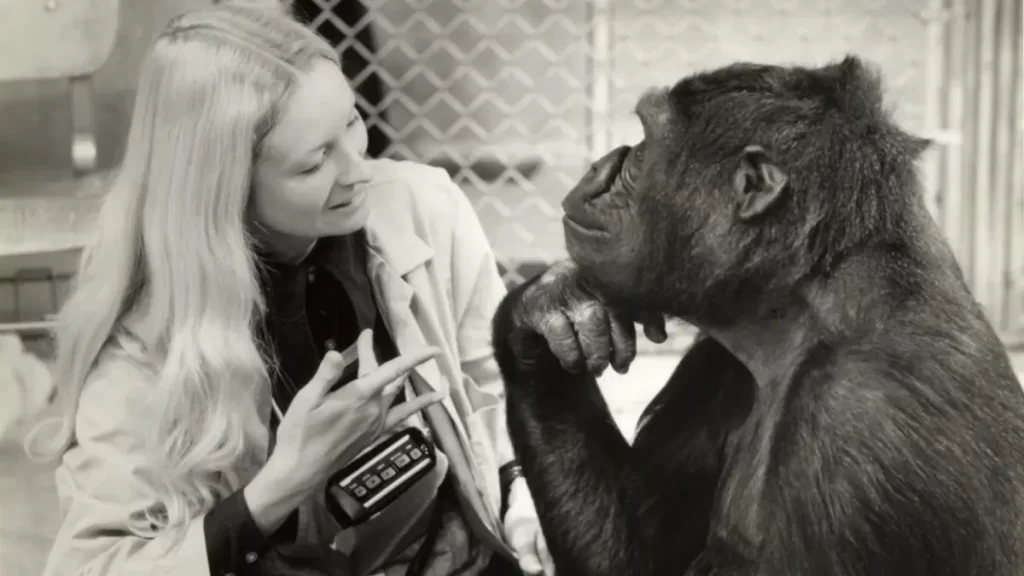

This capability is what sets us apart from our closest animal relatives. While the gap in raw intelligence between a human and a gorilla may not be as vast as we often assume, the gap in our ability to manipulate abstract concepts through language is profound. A gorilla can communicate about its needs, emotions, and even engage in simple problem-solving, but it does not dissect the spectral signatures of atoms or ponder the nature of distant stars. These are uniquely human pursuits, made possible by our capacity to use language as a tool for abstract thought and precise analysis.

Language, therefore, exponentially increases our power and understanding, enabling us to transcend the immediate and the tangible. It allows us to explore realms far beyond the reach of our physical senses, whether through the intricate dance of mathematics or the poetic expression of the ineffable. But we must also recognize that language, for all its strengths, is not the thing itself. It is a map, not the territory; a representation, not the reality. When we speak of love, death, or the cosmos, we are not capturing these experiences in their entirety but rather illuminating a facet of them through the lens of words.

This understanding is crucial for those who are recovering from a background of religious fundamentalism, where language often plays a central role in defining the contours of belief. Religious texts and doctrines use language to shape reality, to create a framework within which the world is understood. But just as a telescope can only reveal a portion of the sky, religious language reveals only a portion of truth. To take these words as the totality of reality is to mistake the map for the territory, the symbol for the substance.

As you step out of the confines of strict religious language, you begin to see the broader landscape that lies beyond it. This is not to say that the language of your past was wrong, but that it was limited, like a microscope that magnifies but also narrows the view. In expanding your linguistic horizons, you are not abandoning the truths you once held dear, but rather placing them in a wider context. You are learning to see the world through multiple lenses, each offering a different perspective, each revealing a different aspect of the vast, interconnected reality we inhabit.

In this journey, you are empowered to use language not as a cage, but as a key—a tool for unlocking new understandings, for navigating the complexities of existence, and for expressing the depths of human experience. By recognizing the power and limitations of language, you gain the freedom to explore, to question, and to embrace the fullness of life in all its richness and diversity. The microscope and telescope of language are now in your hands, ready to reveal the wonders that lie beyond the horizon of the familiar.